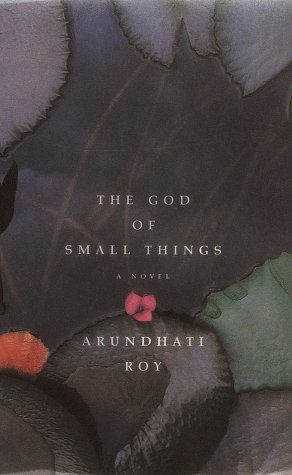

ralentina reviewed The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy

Reclaiming the cliché

5 stars

When I was in my first years of high school, in the early 2000s, this book was all the rage, especially among the leftist teens from my provincial town who were trying out politics in the alter-globalisation movement. I joined a little, from the sidelines, too shy and awkward, and perhaps a bit too arrogant, to be able to feel part. With the perverse logic of the adolescence, I decided that reading such a cool book would be an uncool thing to do. Too cliché. Urgh. Twenty-plus years later, as a white tourist in India, I decided it was finally time and a good way to immerse myself a little in the country. So cliché that it is original again.

I had a lot of time to read and it kept me very good company. The story moves back and forth between the present (i.e. the 1990s) and the 1960s, …

When I was in my first years of high school, in the early 2000s, this book was all the rage, especially among the leftist teens from my provincial town who were trying out politics in the alter-globalisation movement. I joined a little, from the sidelines, too shy and awkward, and perhaps a bit too arrogant, to be able to feel part. With the perverse logic of the adolescence, I decided that reading such a cool book would be an uncool thing to do. Too cliché. Urgh. Twenty-plus years later, as a white tourist in India, I decided it was finally time and a good way to immerse myself a little in the country. So cliché that it is original again.

I had a lot of time to read and it kept me very good company. The story moves back and forth between the present (i.e. the 1990s) and the 1960s, when siblings Rahel and Esta were children, living with their mother Ammu, their grandma, and a host of other relatives. They childhood is a sort of creepy lost paradise: happy and tragic, dark but not as dark as the lives that await them. Gender, class and cast are grappled with in a way that felt, to me, quite useful. All the characters felt to me very believable and three-dimensional, except perhaps for Velutha, the smart, handsome, sweet Paravan-caste carpenter who is uncomfortably saint-like. I should also mention that, although the story is very sad indeed, the language is extremely playful, sometimes in a chuckle-out-loud sort of way.

*Estha had always been a quiet child, so no one could pinpoint with any degree of accuracy exactly when (the year, if not the month or day) he had stopped talking. Stopped talking altogether, that is. The fact is that there wasn't an "exactly when." It had been a gradual winding down and closing shop. A barely noticeable quietening. As though he had simply run out of conversation and had nothing left to say. Yet Estha's silence was never awkward. Never intrusive. Never noisy. It wasn't an accusing, protesting silence as much as a sort of estivation, a dormancy, the psychological equivalent of what lungfish do to get themselves through the dry season, except that in Estha's case the dry season looked as though it would last forever.

Over time he had acquired the ability to blend into the background of wherever he was--into bookshelves, gardens, curtains, doorways, streets--to appear inanimate, almost invisible to the untrained eye. It usually took strangers awhile to notice him even when they were in the same room with him. It took them even longer to notice that he never spoke. Some never noticed at all.

Estha occupied very little space in the world*