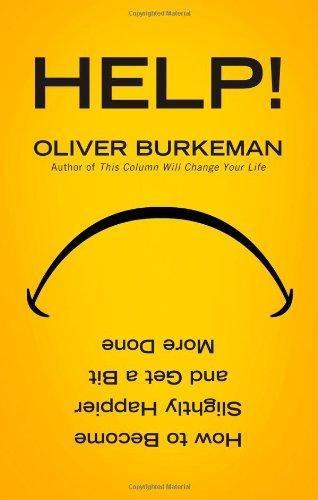

It is no secret that self-help books are my guilty pleasure, and in this respect I felt a sense of kinship with Oliver: he too loves a new to-do list managing system, and is not above the occasional descent into mindfulness, yet holds on to scientific reasoning to mantain a sense of mild superiority. Snap. Also, appreciates dad's jokes.

The book it' s packed with fun facts, such as the news that Thoreau paid someone to come and do his laundry while in his Walden "exile".

It is also a source of references that will make you sound smarter at dinner parties, when you'll be able to casually bring up the Fundamental Attribution Error (FAE) - the human tendency to assume that behaviours are influenced by personality more than by circumstances, for everyone but ourselves (when we lose our tempere is because the situation is unbearable, when others do is because they are neurotic). Or, even better, the Ben Franklin Effect, which refers to the fact that people will like you more after doing you a favour than they will do after receiving one. Perhaps because we dislike feeling in debt, or because we want to align our thoughts to our actions.

Perhaps the most mind-boggling study reported is the one explaining why, statistically, you are likely to have less friends than your friends, be less in shape than the people you see at the gym, and have dated less than your dates (‘Why Your Friends Have More Friends Than You Do'). The reason being that you are more likely to be friends with people with many friends than with solitary wolfes, encounter gym enthusiasts rather than couch potatoes at the gym, etc.

I liked the book's emphasis on common-sense solutions rather than life philosophies. Here are my facourite examples:

The AA urges its members to memorise the acronym HALT: ‘never too hungry, never too angry, never too lonely, never too tired’, because these are the conditions that can trigger a relapse - and generally make us all feel like something is deeply wrong

The science of to--do lists, condensed in 3 principles, according to Burkeman:

Don’t use one list for multiple purposes (eg for general reminders and for things to do right now)Use ‘will-do’, not ‘to-do’ lists (keep your list realistic and do everything on it)The daily list should be a ‘closed list’ (add to it only if it' absolutely necessary)

The best way to time plan (assuming time planning is helpful or necessary in the first place), is to base estimates on past experiences, not on rational calculations, since projects ALWAYS overrun.

And here is a random, beautiful quote by Leonard Cohen that I mean to remember: ‘Forget your perfect offering/There’s a crack in everything/That’s how the light gets in.’

Help! is not a reading that will leave you feeling whole or transformed - I'd go as far as to say that it's the perfect bathroom book, in a positive way, but then again, I doubt Oliver was under the illusion of writing the new War and Peace.

Ultimately, the most useful piece of advice for me is probably this one:’(...) we don’t need new information on how to be happy anywhere near as much as we need a dose of perspective. Advice on how to get more done, feel better, find a soulmate, etcetera, can be useful, but it subtly reinforces the notion that achieving such goals is overwhelmingly important, which fuels stress. Sometimes it’s more helpful to be jolted into remembering that we’d be OK without those things, and that most things we worry about seem absurd a few weeks later.’